January 2022

Author and artist Ruinbow writes for Good Vibrations about their experience of leaving prison during the pandemic.

People imagine that being released from prison would be a euphoric moment, but it is actually really stressful. Counterintuitively, one thing that actually helped me when I was released was that it was lockdown.

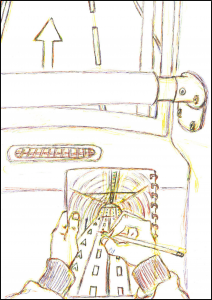

Because I have autism, I can find social situations really difficult. If I got out to see the whole world was doing its thing as normal I would have hit a brick wall. So the fact that everyone was under lockdown restrictions made the transition a bit easier. Getting the train was more comfortable, for example, as I was the only person in the carriage.

There is also a distinct novelty about the whole freedom malarkey, too! Using metal cutlery, the tinkling and clinking against the crockery. Feeling that shiver down your arm as the knife scrapes the plate is quite weird – somehow new and different. Walking down the street is strange too. There are no more gates, no more stopping and waiting for an officer to let you past. You can see far into the distance, and the horizon is so far away. Seeing yourself properly for the first time – that’s new. In prison you only have access to small square mirrors.

While I enjoyed the novelties and freedom, I was stressed about where I was going to live. I was released into a probation hostel. Some people hate being placed in hostels because of the restrictions imposed, but I was relieved to have somewhere to stay, even though it was temporary.

Finding work was much harder than I thought it would be

When I was there I started engaging with the Job Centre and Clean Sheet, a charity that supports people with convictions find employment. They helped me keep motivated in my job search. I had a vision whilst in prison that on release I would get a job in a factory or a warehouse, but it seems that a lot of these jobs are advertised and recruited by agencies. It’s not as easy as I thought it would be to get a job in a place like that.

Even if I had managed to get that sort of job, the strict curfew in the hostel wouldn’t have allowed it. In fact, the curfew meant that I had to turn down two other jobs that I was offered. As I had to turn them down due to external factors, I felt motivated to pursue my art, which I discovered in prison. I basically thought, okay, if I can’t work then I’m gonna do some art and work out what my next steps are.

And finding somewhere to live seemed impossible

I always knew that my stay in the hostel would be temporary and that I had three months to find myself appropriate accommodation. I managed to get in touch with various charities, organisations, and the council. However, as I was living somewhere they couldn’t help me, even though the hostel was temporary. Some of the other lads in the hostel were in the same situation. This was visibly affecting them. One person turned to gambling and when he lost all his benefits he got really drunk and was recalled into prison.

The help offered at the time of my release in February 2021 was really slim and the excuse was coronavirus. I didn’t get the support and guidance I required. I was told on the seventh week of my hostel stay that I was going to be leaving the following week. I was confused as my stay at the hostel was supposed to be 12 weeks long. The manager wasn’t there at the time, so I couldn’t raise the issue for a few days. Over the weekend, I was really stressed and found it hard to cope.

The manager decided to keep me there for the full 12 weeks. However, it’s not simple to find somewhere to move to as probation has to approve the address of all properties before you can move in. Housing benefit would cover between £250 and £300 per month of the rent, but it was impossible to find anything within that price range. There were some properties for around £500 a month, but when I contacted the estate agents they told me that because I’m unemployed and do not have a guarantor, they couldn’t rent to me.

I think this is a real problem. Somebody’s living space should not be viewed as a business opportunity. And if you do choose to make money that way, why would you turn away those people that want help? This is indicative of discrimination between the classes. The poor people have to live in a particular part of town, away from the rich people. And this means that everyone loses out – how can true community form when this is the case?

As I was unable to find an alternative, I was placed into a hotel after my 12 weeks in the hostel. A hotel is not a home. It is a roof over your head and nothing more. Other than a kettle, I had no means of cooking or preparing food, so inevitably I was living off Pot Noodles and takeaways. Once a month I would treat myself to an All You Can Eat Buffet and I would go straight for the fruit and vegetables to get some sort of nutrition.

I felt like my life was in someone else’s hands

While I was in the hotel, the council had to decide if I was “intentionally homeless”. If they decide you are intentionally homeless you have to fend for yourself, which basically means be on the streets. If they decide you are unintentionally homeless they have a duty of care to ensure you have somewhere to live.

They took some time to make the decision, which again placed me under stress. Eventually it was decided that I was unintentionally homeless and I moved from the hotel into supported accommodation. The flat I was placed in was classed as shared. There wasn’t nearly enough space for us there, which made things really difficult for me. The other occupant kept opening my bedroom door as well, sometimes as late as one in the morning. This made me feel really anxious and unsafe. Because I have autism it is important I develop routines that work for me, which I was unable to do with this living arrangement. I spoke to my doctor who recommended I live independently to allow me to find routines and to prevent me getting anxious about having to socially communicate with someone.

Finally things are heading in the right direction

After making a series of complaints, I was moved into a bedsit which I am fairly happy with regarding my own space and being able to develop routines. There have been some minor issues like the hob and fridge/freezer don’t work. It means whenever I buy ice cream, I have to eat it all in one go. I suppose the other option would be not to buy ice cream, but I wouldn’t want to hurt Ben and Jerry’s feelings.

The difficulty I have experienced in finding somewhere to live has really got me thinking about attitudes to housing more generally. Recently, I was talking to a woman who privately rents a flat in a block where some properties are owned by social housing. This means that some residents are only paying half of what she is for a similar property. I do understand her frustration, but it shows that the system is built so that people who require help are resented by those who don’t.

And I’m able to focus on what’s important to me

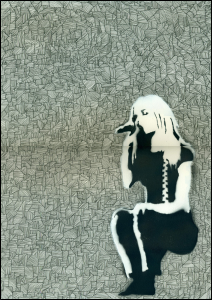

Now my life is moving forward. I always hoped that I could make art my career when I was released, but I imagined it would be a case of getting a job and slowly transitioning to self-employment. Still going to my appointments at the Job Centre while selling some pieces of art has helped me keep the safety net of benefits whilst testing out the self-employment stuff.

My work is now for sale on Prodigal Arts, along with artwork by other prisoners and ex-prisoners, and if you live in or near Chester, you can buy my art from Woodstock Vinyl Record Shop on Brook Street.

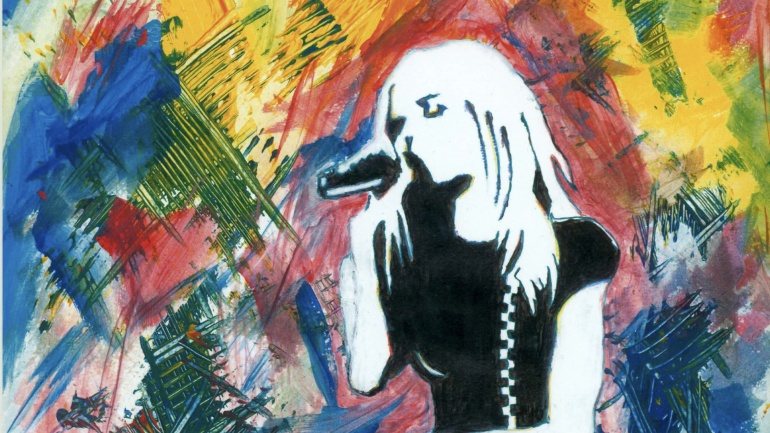

“At least under lockdown I had a roof over my head.”

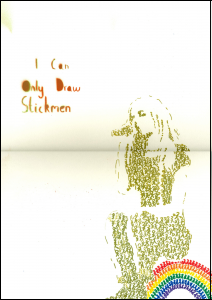

This image shows a homeless guy who is longing for coronavirus and wants it to come back.

The homeless guy is represented by Charlie Chaplin’s “The Tramp” character. I think society just needs to pause and acknowledge that while coronavirus was undoubtedly a negative thing and devastated many lives, to some people it was actually a lifeline. The help that vulnerable people received during the pandemic is now being removed from them. The “wind” in this image that is taking it away is the government.